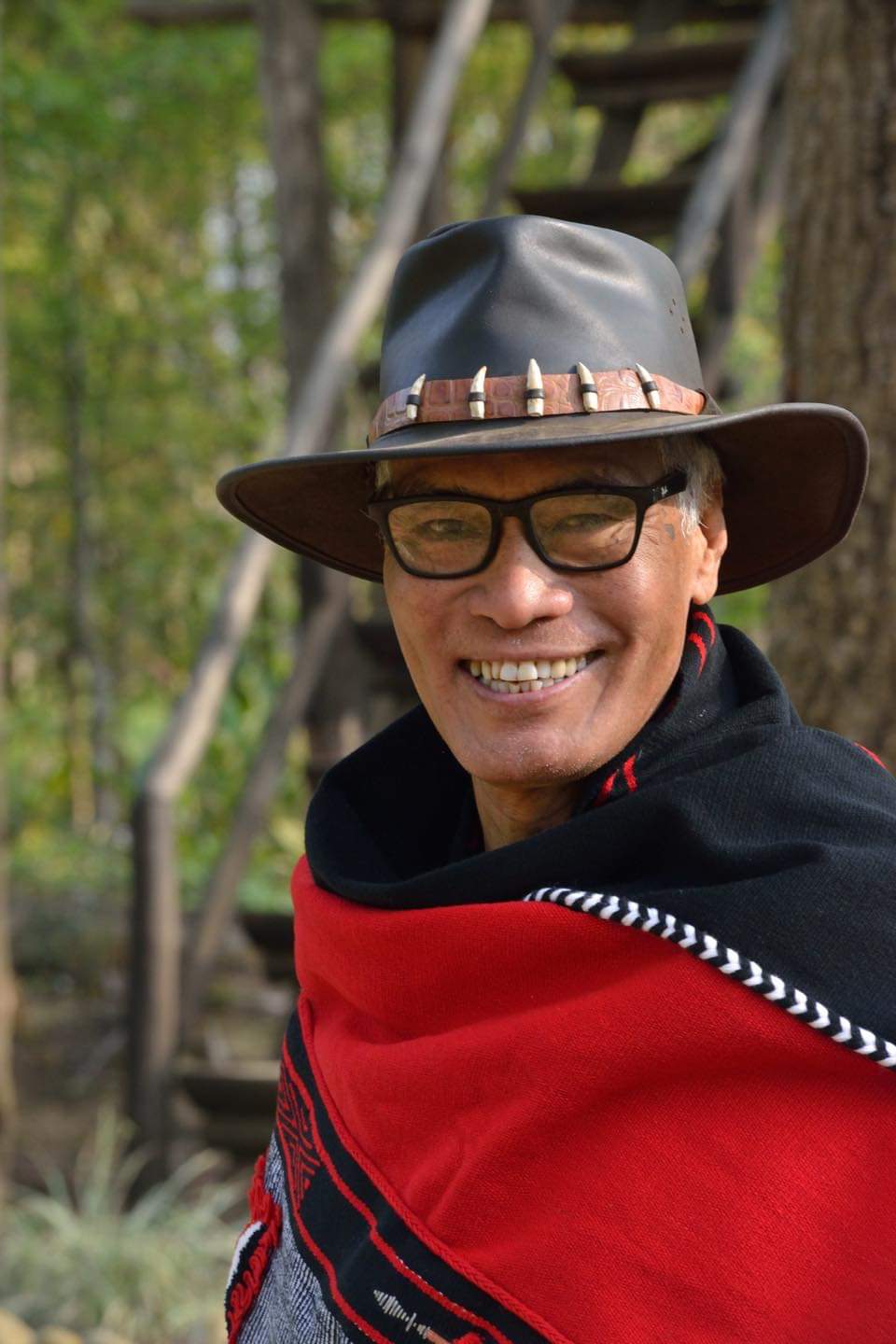

Alan Channer

Environment, Peacebuilding and Communications Specialist

Dr. Visier Sanyü often sleeps in his treehouse. It’s a feature of the 12-acre “Healing Garden” which he created in Medziphema, Northeast India. Sanyü, a retired professor of history and archaeology, likes to quote a Greek proverb to his visitors: ‘A society grows great when old men plant trees whose shade they know they will never sit in.’ Sanyü’s vision is to help foster ‘a society that protects, respects, and connects with the natural world and its cultural life so that every Naga is able to live a fulfilling life’.

He is steeped in the traditions and culture of Nagaland. He grew up in a community practicing jhum – slash and burn cultivation. His father hunted for food. During the Naga insurgency in the late 1950s, Sanyü’s family lived for two years in the jungle, moving between makeshift camps to evade the Indian Army. He recalls an encounter with a tiger. ‘It passed our camp and stopped. Father told us to freeze. We looked at each other for what seemed a long time. Then it melted back into the dense foliage. When I read William Blake’s poem, The Tyger, many years later, I recalled the moment vividly….’

‘The jungle has a spiritual significance for me,’ Sanyü continues. ‘We depended on it and it sustained us. It’s mysterious. It’s like a mother. It gives me solace.’ Sanyü is an elder of his Angami tribe, a former member of the “International Panel of Elders” of Initiatives of Change, a board member of Melbourne Interfaith Centre, and the honorary President of the Overseas Naga Association.

Visier Sanyu’ s TreeHouse

Dr. Visier Sanyu came from Nagaland as a refugee to Melbourne in the 1990s and returned home in 2015 to found a 12-acre ‘Healing Garden’ of restored forest.

In 1996, he began a sabbatical at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at La Trobe University in Melbourne. It was a time of political turmoil and fratricide in Nagaland and he decided to remain in Australia with his family. A friend quipped that he was ‘an indigenous non-Australian who had become a non-indigenous Australian’.

He joined the staff of World Vision and led a successful project, “Welcome to my place”, to foster hospitality for refugees and asylum seekers in Melbourne. Rev Tim Costello, then CEO of World Vision Australia, later wrote the foreword to Sanyü’s autobiography, “A Naga Odyssey”.

Sanyü knew that one day he must return home. ‘It was a vision, a compulsion, a dream all in one,’ he recalls. A clear goal had begun to take shape in his mind: to create a “Healing Garden”. ‘Every Naga family has experienced trauma,’ he points out poignantly. ‘I wanted to create a healing space. For me, a garden was a meaningful way to do it.’

Today, about 50 species of tree grow in Sanyü’s “Healing Garden”. At its heart lie two acres of thick forest, where Sanyü has installed a circle of flat stones in a small clearing, for people to sit and meet. Students, NGO groups, church groups, and different political factions come to sit and share, surrounded by forest. ‘I used to have six acres of teak on this land before I left for Australia,’ Sanyü recalls, ‘but recently I have been cutting the teak, selling the wood and replacing it with different species to encourage wildlife. I’ve also been planting fruit trees and bamboo, of which we have many indigenous species in Nagaland.’

The varied uses of bamboo lie at the heart of the Naga rural economy. From the sharp blade that removes the umbilical cord of a newborn baby, to the finely woven matting wrapped over a body of the deceased, bamboo plays important roles throughout Naga life. Fast-growing and high-yielding, bamboo is used in construction and engineering, to make clothes and handicrafts, as food, in medicine, and as a raw material for pulp and paper. Bamboo draws more carbon out of the atmosphere, and releases more oxygen, than a stand of trees on the same acreage.

Sanyü believes that indigenous agricultural practices should be integrated wherever possible with modern, scientific methods. He highlights several Naga agroforestry systems, notably the pollarding of the Himalayan Alder (Alnus Nepalensis), an indigenous species which fixes nitrogen, in fields around his home village of Khonoma.

Khonoma was the first ‘Green Village of India’, an accolade it received from the Government of Nagaland and the Government of India in 2005. ‘Some of the elders in my village wanted to safeguard the forest and our natural heritage,’ Sanyü remembers. ‘They won the argument over those who wanted to continue logging and hunting as usual.’ In 1998, the 2000 hectare “Khonoma Nature Conservation and Tragopan Sanctuary” (KNCTS) was officially delineated. Tourism took off. Visitors come from all over the world for home-stays in the village, including ornithologists keen to see Blyth’s Tragopan, Naga Wren-Babbler, Great Indian Hornbill and a myriad other bird species.

Sanyü has welcomed Aboriginal leaders from Australia, Maoris from New Zealand, and a Sami leader from Norway to his home in the forest. He believes that the indigenous peoples of the world have an important role to act and to advocate to minimize disruptive climate change and to conserve, regenerate, and re-plant trees.

‘One day a Naga living in America came to visit me here,’ Sanyü recalls. ‘We sat down in the forest. I made tea and served it in a bamboo cup. She told me about her work and her life in America. All of a sudden she started to cry. Then she said, “I am healed”. I’m not a counselor or a monk. We didn’t even talk about healing…. I think it’s something to do with the forest.’